Articles

Dive deeper into certain concepts and read up on important updates.

Dr. Emin Gün Sirer testifies before the US House of Representatives Financial Services Committee

Dr Emin Gun Sirer, Founder & CEO of Ava Labs, testified on 13 June 2023 before the US House of Representatives, House Financial Services Committee on Fostering responsible growth of blockchain technology. Watch his 5 minute introductory speech below. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dr9GD8hdD_U&t=4164s Ahead of his appearance, the Committee published his written testimony which can be read in full below or here Fostering Responsible Growth Of Blockchain Technology Testimony of Dr. Emin Gün Sirer Founder & CEO, Ava Labs, Inc. Before the United States House of Representatives, House Financial Services Committee Chairman McHenry, Ranking Member Waters, and Members of the Committee. It is an honor to be here with you today. I thank you for the opportunity to appear before you as a computer scientist to discuss blockchain technology, its innovative uses, why it is impactful to the economy, and how to understand the use cases that blockchain will support. With an understanding of these key concepts, it is possible to develop sensible regulatory frameworks and ensure the technology will thrive in the United States. There have been several testimonies before this Committee regarding blockchain, but they have been primarily provided by lawyers and business people. To that end, I hope this testimony will provide a helpful overview of blockchain and tokenization from a technology and computer science perspective. I will focus on blockchain’s ability to transform society by making digital services more efficient, reliable and accessible to all. The collective goal is that the United States should seek to enable the free, safe, and responsible proliferation of blockchain technologies and their many applications so that, as a country, the United States and its citizens can benefit greatly from the economic growth that blockchain technologies will enable. My Background I am the founder and CEO of Ava Labs, a software company founded in 2018 that is headquartered in Brooklyn, New York, whose mission is to digitize the world’s assets. Ava Labs is a software company that builds and helps implement technologies on the Avalanche public blockchain and other blockchain ecosystems. We have developed some of the most significant recent technological innovations in blockchain, including the biggest breakthrough in consensus protocols following Bitcoin. Before founding Ava Labs, I was a professor of computer science at Cornell for almost 20 years, advancing the science of blockchains with a focus on improving their scalability, performance, and security. During that time, I consulted with various U.S. government agencies and departments on a range of topics. I have made fundamental contributions to several areas of computer science, including distributed systems, operating systems, and networking, with dozens of peer-reviewed articles (among other things, I am one of the most cited authors in the blockchain space after Satoshi Nakamoto). I hold a National Science Foundation CAREER award and previously served on the DARPA ISAT Committee. I serve as a member of the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s Technology Advisory Committee. But I am perhaps most proud of having helped write a parody of the blockchain space with John Oliver. The Big Picture We are living through a period of unprecedented technological progress and transformation. The computer revolution set this trend in motion, initially with mainframes and later with personal computers. However, these early systems were limited by their "stand-alone architecture," capable only of processing local data and executing local computations. Although they made existing tasks more efficient, they failed to create a multiplier effect due to their lack of network connectivity. The emergence of the internet and, subsequently, world wide web marked a pivotal shift from isolated, local computing to global-scale computing. Architecturally, we transitioned from standalone computers to a "client-server architecture," which enabled us to connect to remote services operated by others to leverage their programs and capabilities. This new paradigm gave rise to digital services that catered to the entire world, created millions of jobs, and solidified the U.S.'s position as a global economic leader. Blockchains represent the next phase in the evolution of networked computer systems. Whereas the client-server systems that power the web today rely on point-to-point technologies to connect clients to servers, blockchains facilitate many-to-many communication over a shared ledger. This allows multiple computers to collaborate, achieve consensus, and act in unison. Blockchain technologies allow us to build shared services in the network. In turn, this enables the development of unique, secure digital assets, more efficient financial services systems, tamper-proof supply chain tracking, digital identity solutions, and transparent voting systems, among many other innovative applications. By harnessing the power of blockchain technology and the digital uniqueness it allows us to create, we can redefine trust, ownership, commerce, recreation, and communications, ultimately transforming how we interact with digital systems and each other. The implications of this breakthrough are far-reaching. Blockchain technology allows us to create systems that reduce costs, increase efficiencies, and gain more control over our digital lives and the virtual world. Additionally, we can establish new kinds of 2 marketplaces, novel digital goods, and services that empower individuals and communities to foster economic growth and social impact. The advancements from blockchain technology will result in leaps forward, just like the internet itself, because they will improve the internet itself. This technology creates a new kind of public good, namely, a shared ledger that can be purposed for a wide range of applications. As we enter the era of customizable blockchains and smart contracts, the fine-tuning of this software will further enhance and improve what the technology delivers today while empowering compliance with relevant regulations. Blockchains and Smart Contracts: Impact Across Applications Blockchains solve a long-standing challenge in computer science: enabling a diverse set of computers worldwide to reach consensus (agreement) on a piece of data and the larger dataset to which it belongs. While it may appear obscure at first glance, this is a crucial building block for solving complex problems that traditional internet systems struggle to address, such as creating digitally unique assets, tracking their ownership, and safely executing business and other processes. In doing so, this technology does not have to rely on humans or intermediaries for its security properties; in fact, it typically provides strong integrity guarantees even in the presence of (partial) system failures. Let me be clear: this ability to leverage distributed or decentralized networks is a desirable goal for many reasons that have nothing to do with securities laws, financial services regulation, or the laws and rules governing other areas of commerce, recreation, and communications. Distributed networks are more resilient, secure, auditable, and available for builders. Blockchain builders did not set out to develop the technology to evade laws and rules. We set out to solve computer science problems. The potential applications for blockchain technology are vast and varied in contrast to the client-server model where many functions are expensive or impossible. Below, I will discuss just some of the key applications and innovations blockchains enable. Blockchains are evolving rapidly Blockchain technology has evolved rapidly in the 14 years since Satoshi Nakamoto introduced Bitcoin to the world. The Bitcoin blockchain pioneered a consensus mechanism – the way that the data is agreed upon by participating computers – popularly and inaccurately known as "proof-of-work." Bitcoin has demonstrated to the world that public, permissionless blockchains are possible. The topic of consensus was known in computer science literature as "byzantine fault tolerance" and research into creating such systems had been funded by the National Science Foundation and DARPA, and involved hundreds of academics, myself included, for multiple decades. Bitcoin solved the problem and proved to the world that this technology could create and maintain a digital asset, as well as establish and transfer ownership over it. Bitcoin has remained up and accessible, even as it weathered numerous attacks throughout its 14 years, without a central authority or controller maintaining its health. In contrast, even the best client-server services built by Microsoft, Google, Amazon, and Facebook have experienced numerous outages during the same timeframe. Computer scientists did not stop there. Subsequent blockchain technologies have expanded this core functionality. Most notably, Ethereum introduced the concept of smart contracts, self-executing programs encoded on blockchains. Smart contracts can facilitate all manner of applications, including currently popular ones like peer-to-peer lending, social networks, digital collectibles such as NFTs and gaming skins, and the tokenization of real-world (traditional) assets on a single chain governed by a uniform set of rules. The latest breakthrough in blockchain architecture is known as multichain blockchains. In these systems, developers can create chains with custom rule sets, execution environments, and governance regimes tailored to their needs. Not only does this level of customization unlock use cases previously not possible on blockchains with single rule sets, but it also isolates traffic and data into environments purpose-built for a task or application. Examples of these systems include Avalanche and Cosmos, which enable the creation of specialized blockchains, sometimes referred to as subnets or app-chains, that can be compliant by design. For instance, SK Planet, a company in South Korea, recently created a specialized blockchain on Avalanche that onboarded more than 58,000 fully identified customers in its first few days. Additionally, Ava Labs is working with Wall Street firms to create a specialized institutional blockchain. With a multichain architecture, operators have complete control over who can access the chain, who secures it, what token, if any, is used for transaction fees, and more. There is a general trend here. Blockchain technology is evolving rapidly and naturally progressing towards making itself more flexible and secure. In other words, it has been through code that many challenging issues have already been addressed. The lesson from these developments is clear: Policymakers should enunciate clear objectives based on the particular implementation of the technology (that is, the activity it is used for), while leaving the mechanisms of achieving those objectives up to experts to determine. Because we can customize blockchain implementations, it is easier than ever to regulate the implementation rather than the technology, and achieve neutrality of regulation. Regulation in The Token World Blockchains are technologies that allow us to build resilient and fault-tolerant applications. They are, in effect, openly programmable platforms that their users can interact with as if they are a public commons. This powerful construct naturally gives rise to many different kinds of applications and, consequently, tokenization, the creation of digital representations of bundles of rights, assets, and other things. All tokens are not equivalent in their implementation or function – they must be treated differently according to their essential nature. Tokens cannot simply be lumped together under a single set of regulations because they vary so widely in function and features. A good analogy is paper; we regulate the bundle of rights, assets, or things created by the words, numbers and pictures on the page. Types of tokens include but are not limited to: A real-world asset: A token can be the direct or indirect representation of a traditional asset. For example, one could tokenize land ownership such that each token corresponds to a uniquely identifiable piece of land. In many cases, real-world assets are already regulated, and their digitization into a blockchain format should not necessitate wholesale new regulation. A virtual item: A token can represent a piece of digital art, a collectible, a gaming skin, and more. These can be varied in function and form as well. They can range from simple non-programmable pictures, a common use of NFTs, to complex assets, some used in games, that can encode all sorts of functions and features of the asset directly inside the asset itself. Pay-for-use: Public blockchains constitute shared computing resources that must be allocated efficiently. A token is the perfect mechanism to meter resource consumption and prioritize important activities. Such tokens are sometimes known as "gas tokens." For example, BTC is the gas token of the Bitcoin blockchain, ETH for Ethereum, AVAX for Avalanche, and so on. Without gas or transaction costs, a single user or small group of users could potentially overwhelm the blockchain, similar to a denial of service attack, making the blockchain unusable. The list above covers expansive categories... But remains just a snapshot of what is happening and what is possible. I encourage you to review our Owl Explains educational initiative for more information. As a matter of first principles, the determination of the regulatory regime must start and end with the functionality and features of the token, not the technology used to create it. At Ava Labs, we call this sensible token classification. Let me be clear again: Tokenization was not created to evade laws. It is the natural product of blockchain technology and an improvement that blockchains offer over traditional systems, just like computer databases were an improvement over paper filing cabinets. In addition to sensible token classification, regulations that pertain to tokens must be devised in a manner that can be enforced at a layer that has access to the necessary information for enforcement. In the same way that we do not expect internet routers to check the verity of content sent on social media applications, we cannot impose a regulatory burden on technology layers that are unaware of the content or operations carried out on-chain. The platforms already provide features, such as lockups and transfer restrictions, that can assist in coding these limitations. Enhancing Market Efficiency, Transparency, and Oversight Blockchains and smart contracts can be the foundation of a more transparent and efficient financial system that enables all participants to share a level playing field. This includes regulators, who can have greater visibility than ever before into the actions and activities of all market participants. Privacy remains an important component of any system. Developing these new ways of providing and regulating financial services should incorporate personal privacy. These improvements can only come with the support and collaboration of regulators and policymakers by providing sensible laws and regulations that allow for the responsible growth of the technologies. How has this played out in the wild? A perfect example is the trustworthiness of exchanges. Last year saw the failure of several crypto-asset exchanges, most notably FTX. Make no mistake: these failures were not failures of blockchain technology. They were failures of traditional custodians who were supposed to secure user deposits. Not a single major decentralized exchange was affected by a similar failure. Blockchain technology is purpose-built to eliminate this reliance on centralized intermediaries, who can jeopardize user funds, market integrity, and other desired features of a well-functioning system. In addition to on-chain custody and transacting, a more recent breakthrough known as enclaves enables new marketplaces where code severely constrains what even the owner and operator of the marketplace can do. This innovation can rule out unwanted behaviors like front-running, stop-loss hunting, and breaches of privacy that challenge market integrity. Ava Labs’s own Enclave Markets is at the forefront of this innovation, which we call fully encrypted exchanges. Another example that points up the benefits of engaging in activities on-chain as opposed to with centralized parties comes in the lending context. Last year saw major failures of lenders and borrowers who conducted their activities off-chain, while the major on-chain lending platforms weathered the stormy markets mostly unscathed. These protocols adeptly navigated liquidations and collateral calls in rapidly falling markets, due to their reliance on over-collateralization and automated systems. While there is no panacea, the evidence so far points to the success of decentralized networks in managing stress conditions much better than centralized counterparties. These results are in line with what blockchain design predicts. Stablecoins as the Digital Gateway for the U.S. Dollar Stablecoins, which are predominantly denominated in United States Dollars, are expanding globally because they are a superior way of holding dollars. Stablecoins not only enhance the user experience—by increasing the velocity of capital and reducing the cost of transferring it—but also cater to a growing demand for stablecoin dollars among those facing economic uncertainty and hyperinflation in their local economies. By transforming the dollar's capacity to retain value into an accessible product outside the U.S., stablecoins help individuals protect their life savings from fluctuations in the value of their local currencies and from being stolen by criminals and other rogue actors. This potential can be realized with appropriate regulation, which allows for the responsible growth of stablecoins through new technologies and configurations. Blockchains Can Accelerate Recoveries from Climate Disasters with Insurance Consider the emerging property insurance crisis catalyzed by more frequent and extreme climate events. State Farm, the largest property insurer in California, announced it will no longer provide insurance due to the risk of wildfires. Insurers in Texas, Florida, Colorado, and Louisiana have felt the same pressure to stop provisioning insurance, increase rates, or find backstops for insolvency. Who will communities in these states, and in the U.S. as a whole, rely on to insure their homes and economic futures? If the industry consolidates as bankruptcies hit smaller regional insurers, how will that risk be managed? Using smart contracts and the Avalanche network, Lemonade Foundation is now providing insurance to more than 7,000 farmers who previously only had access to products with unaffordable premiums or delays in payout that had lasting, multi-season impacts. These premiums were not economically feasible for the organization due to the manually-intensive processes now condensed into a single smart contract. As another example, in 2019, the U.S. government completed the accounting for Hurricane Katrina disbursements, a full 14 years after its catastrophic impact in 2005. The delays stemmed partly from the difficulty of achieving agreement among the many stakeholders participating in this process. In 2012, Superstorm Sandy damaged almost half a million homes and incurred roughly $50B in damages. The same gaps in insurance payouts stifled urgent recovery efforts across the East Coast. Families who had paid their premiums for years were given pennies on the dollar to rebuild their lives. By the time their lawsuits led to action and more financial payouts, the damage had been done, and scars set on these communities. Blockchain-based distributed ledgers can significantly streamline such processes, and our company is collaborating with Deloitte under a FEMA contract to develop and implement this technology. Supply Chain and Fighting Counterfeiting Global supply chains are facing challenges relating to the expedited demand for goods and pandemic-driven strains, including our most security-critical infrastructure. When supply chain problems hit, they can be especially problematic, and when there is fraud, the problems are exacerbated. Blockchains and smart contracts can help secure and validate supply chains for various global sectors. Blockchains can perform supply-chain management to provide a reliable and transparent record of a product's origin and authenticity. The Tracr platform from De Beers has shown how to accomplish this for diamonds, while other deployments have addressed fields ranging from luxury goods to concert tickets. Blockchains can be vital tools to fight the counterfeiting of medical supplies, pharmaceuticals, food products, and consumer technologies that directly affect our communities and your constituents. Upcoming Technological Improvements While there have been highly-publicized exploits of smart contracts, the space has significantly matured since its early days, and new technologies stand poised to improve the safety of on-chain assets and applications. The potential risks relating to smart contract-based systems have centered around flaws in implementation, such as poor coding and negligence in following best practices, rather than fundamental issues inherent to smart contracts or blockchain technology. Just as the internet software stacks were weak in the 1990s, smart contract programming tools are in their infancy. The space has rapidly evolved to use code audits and other techniques to certify that smart contracts uphold safety standards, giving rise to a burgeoning field of software threat analysis, certification, and verification services. In addition, we are seeing the emergence of automated tools for program verification and model checking to help find bugs that human eyes cannot easily locate. These techniques operate even before programs are deployed to root out bugs before they can affect anyone. Finally, there are new mechanisms, such as run-time integrity checks, smart contract escape hatches, and automated limits on money flows that operate in real-time to help contain the effects of any unintended errors that might pass through to production. Systems that have employed best practices, such as lending platforms and well-designed bridges, such as the ones Ava Labs has built, have seen billions of dollars pass through their contracts without compromise. Given my background in academia and research, I am confident that the space will develop even stronger techniques for ensuring the correctness of smart contract software. One of the spillover effects of this activity will be better integrity and safety for all software, including software not related to blockchains. Technological Competitiveness and Risk of Inaction As we stand at the precipice of this new era, it is imperative that we nurture and support the development of this revolutionary technology. By doing so, we can unlock its full potential and ensure that the United States remains at the forefront of innovation, propelling the next generation of internet technologies and ushering in great economic growth. Responsible actors in the blockchain space want sensible laws and regulations that incentivize growth and good behavior, punish bad actors, and elevate the users of blockchain networks. The community stands ready to provide guidance to policymakers to achieve those aims. However, without sensible frameworks and collaboration, there is a clear path to losing technological leadership to other countries. The United States won the first wave of the internet revolution precisely because it enabled responsible freedom to innovate. The United States must follow the same path of enabling free but responsible growth of blockchain technology while carefully and intelligently classifying and regulating blockchain applications and tokens. Otherwise, there are two critical paths of failure for any regulatory framework. First, the blockchain platforms themselves become regulated at the protocol layer. This would be the equivalent of regulating internet protocols, which would have doomed information technology and the vibrant internet we have today. Second, the tokens and smart contracts created with blockchains are lumped into homogenous and incompatible categories. This would be the equivalent of regulating a social media application like we regulate a consumer health care application. Instead, tokens and smart contracts must be analyzed case-by-case and regulated carefully based on their function and features. As we move towards a more digitally-native world, aided by AI, virtual reality, and a work-from-home society, we will have to rely increasingly on digitally-native transfer and programmability of value. Blockchains are the clear technological answer to these needs and are definitively synergistic with the global economy. The addressable market for digitizing the world's assets and transferring value safely across the internet is greater than the sum of all the value of all existing assets. Failure to see the power of blockchain technology – whether due to a lack of understanding or misplaced fears of the technology – will have disastrous consequences. Failure to rapidly provide sensible regulatory frameworks will not only undermine economic growth but also make it easier for bad actors to conduct illicit activities. Finally, it is essential to remember that just as there are good people committed to public service, there are also good people committed to building technologies to improve lives. By working together, we can lay the foundation for trustworthy, efficient, and self-enforcing systems that serve as the foundation for our modern economy.

How Should We Regulate Crypto/Web3 Cybersecurity?

Cybersecurity is all about the financial incentives. Getting cybersecurity regulation right means using the threat of regulatory fines to align financial incentives so that companies do the right thing. Compared to most existing cybersecurity regulations, however, the financial incentives in cryptocurrency/Web3 are very different. Most existing cybersecurity regulations aim to improve the security of consumer PII and personal information that companies hold. Because the theft (more accurately: copying) of consumer PII by hackers during a data breach does not result in an immediate financial impact to a company's bottom line, companies have historically paid less attention to cybersecurity than they should. Since the free market financial incentives for companies to secure consumer data are poor, regulators have naturally stepped in with a regulatory stick (where the free market carrot has failed). The financial incentives in crypto, however, are very different. With crypto, if you are hacked and your crypto is stolen, you've lost your own assets. That's a huge incentive to do cybersecurity properly. Here are five major takeaways that regulators should consider: For companies self-custodying their own crypto, financial incentives are already 100% aligned. If Company X holds $1 million in cryptocurrency, and a hacker steals it, the company just suffers an immediate financial loss of $1 million. Regulatory fines would not offer any greater financial incentives for Company X to do the right thing. For companies that hold someone else's crypto assets, the financial incentives are not quite so aligned. If a company custodies $100 million, only $1 million of which is their own, and a hacker steals all $100 million, then the company will simply declare bankruptcy and leave their debtors with nothing. An example might be a centralized crypto exchange, or a DeFi service built on top of a smart contract. In these kinds of situations it might be appropriate for regulators to require minimum security controls to protect users. Getting cybersecurity regulations right is hard. The result of cybersecurity regulations in other areas (such as consumer PII or PHI) has been that companies will do the bare minimum to satisfy cybersecurity regulations, and no more. Finding the right balance between creating regulatory financial incentives without unduly stifling innovation becomes a difficult balancing act. Hackers don't care about regulatory compliance. Cyber defenders have to be right every single time, and attackers only have to be right once. Unlike environmental protection regulation, where accidental oil spills or illegal toxic waste dumping is the primary concern, in cybersecurity we are worried about malicious third parties acting outside the reach of the law in countries like North Korea or Russia. There is frequently no legal recourse in the event of a crypto hack. Crypto startups need to front-load security spending. In most startups, the biggest risk is going out of business, not cybersecurity risk. As a result, startups tend to run very insecure for a couple of years until they are financially successful enough to go back and fix things (so-called "tech debt"). However, this approach does not work in the crypto space, where hackers frequently prey on lean, insecure startups that enjoy overnight financial success. Forcing crypto startups to frontload security expenditure from the beginning could be a key lever of effective regulation. Cybersecurity risk in the crypto/Web3 space is high... ... higher than in most other verticals, because we're not talking about the security of information, but about real, fungible, and non-reversible financial assets. The stakes are high and companies in the crypto space take security seriously. Financial incentives to do security properly align much more closely in the crypto space than in almost any other vertical. The alignment is not 100% perfect, but it is close enough that regulators should take a "light touch" approach to crypto cybersecurity regulation.

IRS seeks feedback on definition of NFTs

The U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) announced this week that it is seeking feedback regarding the tax treatment of NFTs as collectibles under tax law that will inform upcoming guidance. Specifically, it is soliciting comments on: The treatment of NFTs as collectibles and other questions such as whether the IRS has accurately defined NFTs; Its use of a look-through analysis to determine whether a digital asset may be taxed as a collectible, as opposed to a capital asset, which is currently the treatment used for sales or exchanges of digital assets; The factors it should use to consider whether an NFT is a collectible for tax purposes; Whether there are any issues with applying the tax treatment for collectibles to individually directed accounts under a qualified plan; and What other guidance related to NFTs would be helpful. Comments are due on June 19, 2023. Importantly, the IRS defines an NFT as "a unique digital identifier that is recorded using distributed ledger technology and may be used to certify authenticity and ownership of an associated right or asset." And it acknowledges that "[o]wnership of an NFT may provide the holder a right with respect to a digital file (such as a digital image, digital music, a digital trading card, or a digital sports moment) that typically is separate from the NFT." (footnote omitted). It also acknowledges that NFTs may provide certain rights, such as attending an event, or proving ownership of a physical item. This helps distinguish NFTs, which are not intended to be financial in nature, from other types of digital assets. In other words, the IRS is taking a step towards a sensible token classification system by expanding on its guidance for digital assets. The notice provides that the proposed treatment of NFTs as collectibles would fall under a provision of the tax code that applies to collectibles held within individual retirement accounts, and the sale or exchange of a collectible held for over one year would be subject to a maximum 28%perc capital gains tax (as opposed to a lower tax rate for capital assets). Per the IRS’ look-through analysis, an NFT would be treated as a collectible for tax purposes if the asset or associated right tied to the NFT also meets the definition of a collectible. The tax laws state that works of art, rugs or antiques, metals or gems, stamps or coins, alcoholic beverages, or certain tangible personal property are considered collectibles. For example, an NFT representing ownership of a stamp would be treated as a collectible. On the other hand, NFTs representing objects outside of this category would not be classified as collectibles. Where further analysis is required is whether a collectible constitutes a “work of art,” an area where the IRS is requesting feedback.

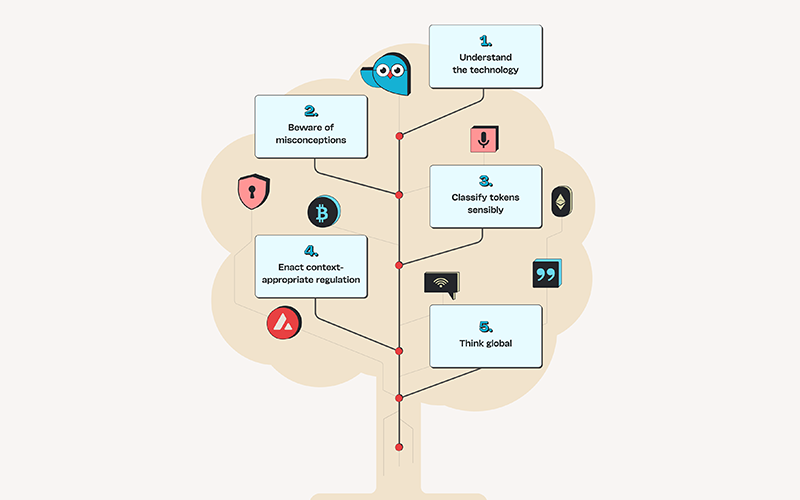

Introducing the Tree of Web3 Wisdom

Introducing the Tree of Web3 Wisdom - 5 branches to guide policymaker thinking The world of Web3 is rapidly evolving, while policymakers keep up with the latest developments to enact effective, sensible regulation that nurtures important technologies and protects consumers. This is a global phenomenon. Japan continues to update its first-in-the-world comprehensive cryptoasset regulation; Singapore regularly iterates on its regulatory regime, as does South Korea and many small Asian jurisdictions. The EU is on the cusp of implementing its Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation (MiCA), while various US regulatory agencies continue the work assigned to them in the President’s Executive Order from March 2022. The US Congress is also hard at work with hearings and draft bills. Against this backdrop, the Tree of Web3 Wisdom provides a helpful framework for understanding the key aspects of Web3 technology and which first principles are important for regulating it. Let's explore the five branches of the Tree of Web3 Wisdom and their implications for policymakers. The first branch of the tree is to understand the technology. Before regulating Web3, it's essential to have a deep understanding of blockchain technology. Blockchain allows for digital ownership and transfer of value across the internet, with enhanced security, transparency, auditability, programmability, and scale. It also enables users to program on these databases to create applications that are part of a larger tech stack for anything their creativity can imagine. This technology has the potential to empower communities, remove friction, verify credentials, and create new efficiencies in commerce. It's essential for policymakers to understand the capabilities of blockchains and the problems they solve to see the potential benefits and risks involved in its implementation. The second branch of the tree is to beware of misconceptions. Blockchain technology isn't just about financial transactions. It's a new infrastructure for the internet, providing a decentralized system that promotes transparency and security by having no single point of failure, no single source of truth, and no single entity or authority with the power or obligation to change data or transactions. Crypto assets and blockchain are not synonymous. Blockchains facilitate crypto assets, but they also facilitate many other types of activities by allowing data integrity and digital uniqueness through tokenization. Crypto assets are a way to digitally represent something on a blockchain. Decentralized systems promote transparency and security by having no single point of failure, no single source of truth, and no single entity or authority with the power or obligation to change data or transactions. Decentralization does not necessarily mean "permissionless and public," and it is crucial to understand that blockchain technology can be permissioned and private too. DeFi is more than just trading financial instruments–it is an avenue to democratize commercial systems by using blockchains and smart contracts to replace traditional intermediaries with built-in trust mechanisms. NFTs are not just for collectibles and art with revenue streams. An NFT is a type of token that is digitally unique, allowing for more specialized representations regardless of the industry. The third branch of the tree is to classify tokens sensibly. A token is a digital representation of something on a blockchain, such as an asset, item, or bundle of rights. Tokenization allows the item's ownership to be established and transferred globally on one or more blockchain networks. A sensible classification systemrecognizes the nature of a token based on the item or rights it represents, whether it's a physical item, intangible item, a type of service, or simply a native token integral to the functioning of a particular blockchain network. Treating all tokens as financial instruments or the trading of tokens as financial activity will unnecessarily limit their use in commerce, communications, entertainment, recreation, governance, and anywhere else establishing ownership. It's essential to classify tokens sensibly to understand their utilization, valuation, and legal classification and, therefore, their appropriate regulatory treatment. The fourth branch of the tree is to enact context-appropriate regulation. Just like plants need specific care depending on their nature and location, blockchain and crypto require appropriate regulation based on their context. Responsible actors want sensible policies that incentivize growth and good behavior, punish bad actors, and regulate intermediaries. Appropriate laws and regulations traditionally have been determined according to the type of asset or technology and its context, i.e., how it is being used, by whom, and the associated risks. This same approach should apply to blockchains and tokenization, which are just a new way of establishing ownership and transferring value. It's important to note that innovative programs and features on a blockchain are run by autonomously-functioning code, and their role needs to be carefully considered when regulating. In enacting context-appropriate regulation, policymakers must also consider the impact of blockchain and crypto on individuals and society. Finally, the fifth branch of the tree is to think global. This last branch of the Tree of Web3 Wisdom emphasizes the ongoing evolution of blockchain technology and the endless possibilities for its use in various fields. The potential applications of blockchain technology go beyond financial transactions and encompass a wide range of industries, such as healthcare, supply chain management, voting, and identity verification. Just like the internet, blockchains and crypto assets are global and require a coordinated regulatory approach based on certain "first principles," including disclosure, market integrity, disclosure, anti-fraud, privacy, and operational integrity. As blockchain technology continues to mature and evolve, it will likely provide even more benefits, such as greater privacy, scalability, and interoperability. Quality builders, including developers, entrepreneurs, and investors, will play a crucial role in driving innovation and creating new and exciting ways to use blockchain technology. Just look at Lemonade Foundation, as one example. However, this ongoing innovation and growth also requires sensible regulation to strike a balance between fostering innovation and protecting consumers and the broader economy. In conclusion, the Tree of Web3 Wisdom provides policymakers with five critical principles to guide their thinking when considering how to regulate blockchain, tokenization, and Web3. By understanding the technology, avoiding misconceptions, classifying tokens sensibly, enacting context-appropriate regulation, and thinking globally, policymakers can create a regulatory framework that fosters innovation while supporting safety and security for all stakeholders. Read the Tree of Wisdom in full here.

FASB Delves Into Sensible Token Classification

The Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) is seeking feedback on its proposed treatment regarding the accounting for and disclosure of a narrow category of crypto assets. The proposed Accounting Standards Update (ASU) is intended to improve information provided to investors about a company’s crypto asset holdings. Comments are due June 6 and may be submitted through the website or emailing comments to director [at] fasb [dot] org, File Reference No. 2023-ED200. The ASU sets forth the accounting treatment for the class of crypto assets that meet the following criteria: Are intangible assets; Do not provide the asset holder with enforceable rights to, or claims on underlying goods, services, or other assets; Are created on or reside on a blockchain; Are secured through cryptography; Are fungible; and Are not created or issued by the reporting entity or its related parties. Sound familiar? This follows the principles discussed in the sensible token classification systemand in particular the class called “native DLT tokens”! The IRS also recently discussed token classification. See our note on the guidance release, available here. Owl Explains is elated by these developments because proper token classification is Branch 3 of our Tree of Web3 Wisdom. Under the ASU, reporting entities would need to measure at fair value changes in net income associated with this class of asset during each reporting period. Meanwhile, transaction costs related to acquiring this type of crypto asset, such as fees and commissions, would be recognized as an expense as incurred absent industry-specific guidance that the reporting entity capitalize those costs. The ASU would also require these crypto assets to be presented separately from other intangible assets (whether tokenized or traditionally represented) on a reporting entity’s balance sheet and changes in the fair market value of crypto assets would be separate from changes in the carrying amounts of other intangible assets in the income statement. Further, if this type of crypto assets are received as noncash consideration in the ordinary course of business and they are almost immediately converted into cash (i.e., as payment for goods and services), then the entity would be required to classify those cash receipts for goods and services paid in crypto assets as cash flows from operating activities. The ASU also lists the information that would need to be disclosed with respect to crypto asset holdings. Notably, based on these criteria, NFTs would likely be excluded from the ASU since NFTs often provide holders with certain rights to goods and services and they are not fungible, as opposed to fungible crypto assets that are used for general purposes on a blockchain.

Why fungible crypto assets are not securities

Why fungible crypto assets are not securities The speakers at our Owl Explains Hootenanny last week are co-authors of the most thorough analysis to date of the burning question of whether fungible crypto assets are - or are not - securities. (Spoiler alert – mostly they are not.) Lewis Cohen, Freeman Lewin and Sarah Chen from DLX law firm have analysed the US Securities Acts, the ‘Howey test’ on investment contracts (more on that below) and 266 pieces of case law where the Howey test was applied to different scenarios. The resulting paper is 180 pages long. But fear not! This owl has served up this pithy appetiser to whet your appetite for the full feast which you can find here So what’s this all about? The flurry of Initial Coin Offerings (ICOs) a few years ago has led some regulators to conflate the token sales in an ICO and the crypto assets involved in them and seek to apply US securities laws to both. The authors of this paper do not dispute that the fundraising activity of an ICO – inviting investors to purchase crypto assets in a fledgling project with the hope of making a profit – might indeed involve an investment contract and that securities law would often apply. What they dispute is whether and when the crypto assets themselves qualify as ‘securities’ according to current laws and regulations. Just as oranges, chinchillas, whiskey barrels and stamps can form part of an investment contract but are not themselves securities, the same goes for crypto assets. (This owl particularly enjoyed the bit about how chinchillas are not securities – of course they aren’t – they’re lunch). They also challenge the notion that ‘once a security, always a security’ that continues to classify a crypto asset as a security well beyond the context of an ICO when the crypto asset may be performing all manner of other functions that do not involve an investment contract. So what should regulators do instead? The co-authors recommend that the status of a crypto asset can only be determined by first understanding the true nature of the crypto asset – and then by understanding and applying case law and legal scholarship on investment contract transactions. And that is exactly what the article does – exploring first the nature of crypto assets and then delving into case law and legal scholarship to explore when an investment contract does and does not exist. Why does this matter? It matters more than ever right now as policy makers and regulators, particularly in the US, are leaning towards deeming many, even all, crypto assets to be securities without going through this exercise of interrogating the nature of the asset and the transaction. And that matters because if all crypto assets are treated as securities even if they represent things that clearly are not – and even when they are clearly not part of an investment contract - regulators risk not only strangling with red tape the innovation and promise of Web3, but also causing confusion for all manner of items like the aforementioned chinchillas. So when is a crypto asset a security? A crypto asset is a security either by its very nature (e.g., a stock or bond on blockchain). When it is part of an investment contract according to the Howey Test, well, the crypto asset is not a security but the investment contract is. Clearly crypto assets cannot be assumed to be securities by their very nature – because a crypto asset can represent literally anything at all. They may occasionally be – but equally (and more often) they may not be. So where the asset is not a security by nature, we have to assess whether they might be part of an investment contract as defined by the Howey Test. Still not a security, but the subject of an investment contract. So what is the Howey Test? The Howey test says that an investment contract transaction exists when a “contract, transaction or scheme” involves an investment of money in a common enterprise with an expectation of profits to come solely from the efforts of the promoter or a third party. So the Howey test defines correctly that fundraising by selling crypto assets as part of an ICO might be an investment contract that the securities laws apply to. And while crypto assets are part of that investment contract, they are not themselves securities. But what happens when the fundraise is complete and the crypto assets are being used for other purposes where Howey tells us clearly there is no investment contract? An example could be when they are merely validated, delegated or staked. Or when they are performing as a utility token intrinsic to the functioning of a blockchain. The article does not shy away from the complexity of all this. In fact it opens with a quote from Homer’s The Odyssey where the old man of the sea changes himself ‘first into a lion with a great mane, then all of a sudden he became a dragon, a leopard, a wild boar; the next moment he was running water and then again directly he was a tree’ Why? Because crypto assets can also shape shift in that different circumstances can affect whether a cryptoasset should be treated as a security or not. With this mercurial nature then, regulators and practitioners need to consider each and every transaction and activity concerning a crypto asset on a case by case basis to determine whether there is a security or not. But this isn’t always possible because the information needed to make that assessment is private. So what is the solution? A new law and more engagement from and between the SEC, FTC, CFTC, Department for Justice and state attorneys general. So you mean regulation? Yes. Fundamentally the co-authors call for regulation based on the kind of thorough understanding and legal analysis of crypto assets that this paper provides. Other resources Our wise owl Lee Schneider has written a few essays that talk about these issues and are available here and here.